Ecclesiastes: Don’t Miss the “Point”

Published February 8, 2023

“The words of the wise are like goads, and like nails firmly fixed are the collected sayings; they are given by one Shepherd.” Ecclesiastes 12:11

Icepicks. Arrows. Fishhooks. Drill bits. Needles. What all these objects have in common (besides having two syllables) is that they are tools whose usefulness depends upon the sharpness of their points. However, the same point that makes the tool useful also makes it painful when implemented.

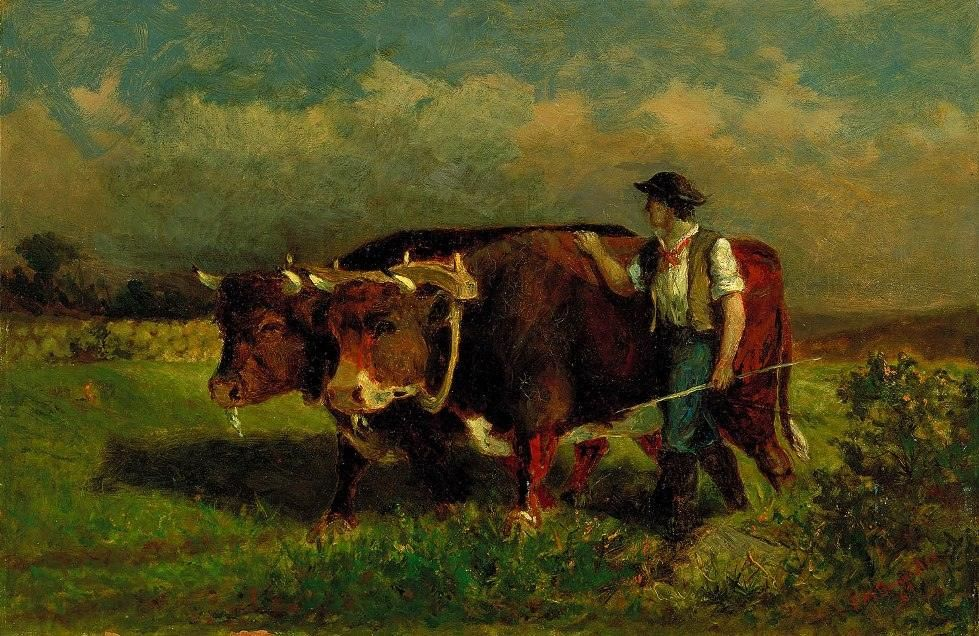

One such tool is a goad, which is a sturdy stick with a pointy end used for driving oxen or cattle (and occasionally killing Philistines [Judges 3:31]). A firm jab with one of these will certainly inflict pain, but this temporary pain will direct the oxen away from real harm. Ecclesiastes 12:11 says that “the words of the wise are like goads.” Ecclesiastes is filled with statements that sting. Its points are pointy, and its conclusions cutting. Reading it will inflict pain, but like the ox goad, it is the kind of pain that God uses for our good.

A Warning

The pointy goads of Ecclesiastes are effective for our instruction, but they make for difficult reading. Just as we are averse to physical pain, we also shy away from words that make us ponder bitter realities. Therefore, my goal in this post is to urge the reader to avoid and in some cases unlearn any approach to Ecclesiastes that dulls its pointy ends. Because these approaches are widespread in the church, I find myself in the same position as Martin Luther, who once said, “This book is one of the more difficult books in all of Scripture, one which no one has ever completely mastered. Indeed, it has been so distorted by the miserable commentaries of many writers that it is almost a bigger job to purify and defend the author from the notions which they have smuggled into him that it is to show his real meaning.” Many more “miserable commentaries” have been written since, but there is nothing new under the sun.

Life without God?

Speaking of the phrase “under the sun,” one common mistake interpreters make is to read this phrase as a technical statement meaning something like “life without God.” According to this view, all of the difficult statements in the Ecclesiastes can be explained by saying that the preacher is presenting conclusions that an unbeliever would reach using worldly wisdom alone in order to show us our need for God. This approach is appealing but too convenient. Proponents of this view have the problem of explaining why a book that’s supposedly all about “life without God” mentions God some forty times, sometimes even in the context of “under the sun” statements (9:9). There are also many conclusions in the book that could only be reached by a believer, yet there are no clear indicators in the text of when the author supposedly switches from the “life without God” perspective to the perspective of a believer. It is better to understand the phrase “under the sun” as a poetic way of referring to life here and now in this fallen world.

A Negative Example?

Another interpretive pitfall to avoid is pitting the conclusion of the book against the rest of it. Some make much of the fact that the beginning and end of the book speak of “the preacher” in the third person, which points to an editor or frame narrator presenting the words of the preacher to the reader. One particularly dangerous version of this approach asserts that the preacher’s words are being presented as a negative example of unorthodox theology that the reader should be wary of. They read “fear God and keep His commandments” in 12:13 as a corrective to the preachers message, not a summation of it. Proponents of this view point to the book of Job as an example, where we are given theologically suspect speeches from Job’s friends who are then rebuked by God at the end of the book for their foolishness. This view is convenient because it resolves the difficulties of the book, but there are two problems with it. First, it incorrectly assumes that the bulk of the book’s teaching is unorthodox (future blog posts will demonstrate that it is not). Second, it misreads the conclusion of the book. Consider the following verses:

“Besides being wise, the Preacher also taught the people knowledge, weighing and studying and arranging many proverbs with great care. The Preacher sought to find words of delight, and uprightly he wrote words of truth. The words of the wise are like goads, and like nails firmly fixed are the collected sayings; they are given by one Shepherd” (12:9-11).

Does this sound like the narrator is presenting a negative example of human wisdom gone awry? Or does he affirm that the preacher’s words are truthful and come from one (divine) Shepherd? Hint: it’s the latter. Therefore, this negative example interpretation must be rejected.

An Exhortation

The words of the wise are like goads, which are pointy and painful. Both of the approaches above attempt to grind down the sharp ends, but a goad without a point is just a stick. Ecclesiastes, rightly understood, will sting. The preacher will inflict us with wounds, but they are the wounds of a friend (Prov. 27:6). Let us not resist the correction of our loving Father or kick against the goads of our good Shepherd.

2 Comments

Carolynn Schnitzer

Ryan,

Neil & I will look forward to getting pricked by the book we have little knowledge of. 😊

Ryan Carpenter (Author)

Amen! Thanks for reading.